A Conversation with Bishop Jacob Owensby

Diocesan convention keynote speaker reflects on hope, connection

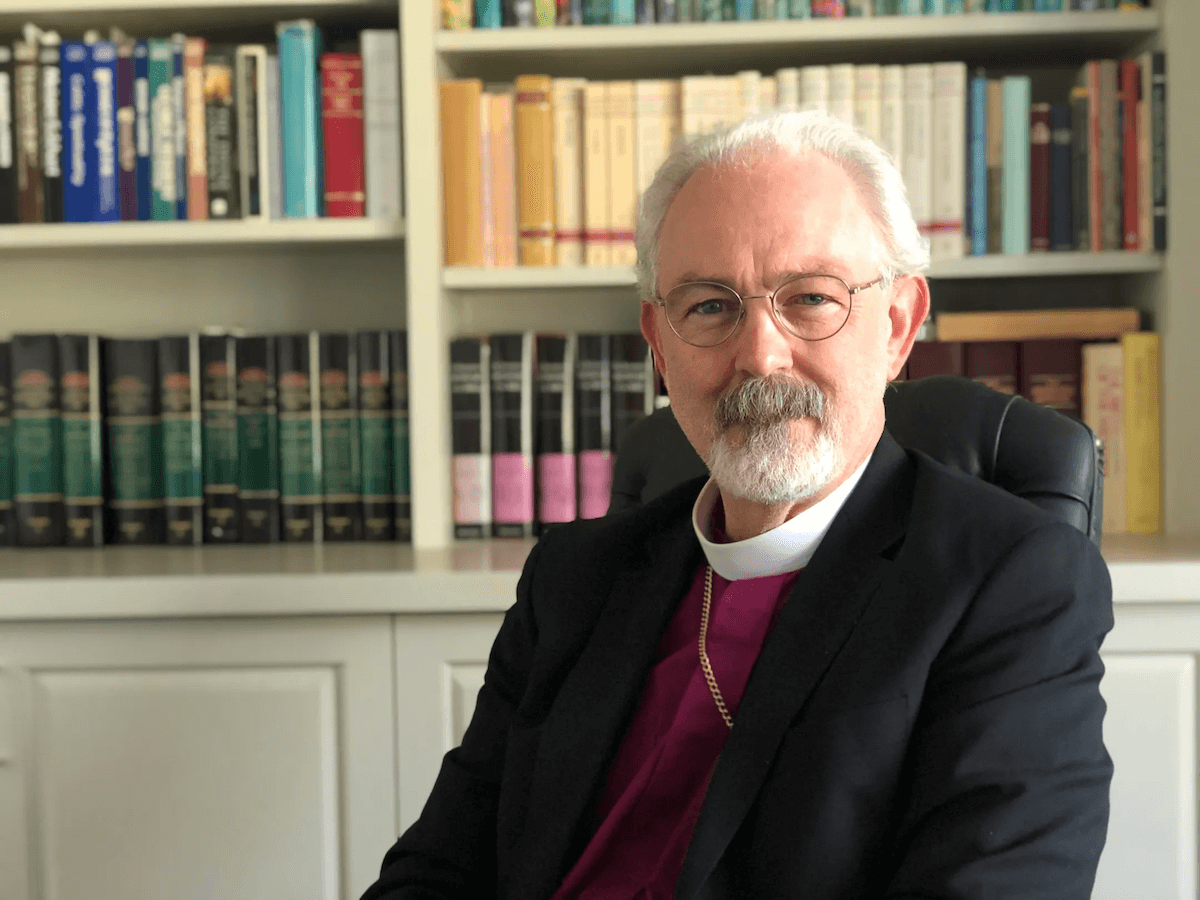

The Rt. Rev. Jacob W. Owensby is the bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Western Louisiana and chancellor of Sewanee, The University of the South. The author of six books, with a manuscript underway, Bishop Owensby also writes a popular blog. Before attending the School of Theology at Sewanee, Owensby earned a Ph.D. at Emory University and was an associate professor of philosophy at Jacksonville University. He and Bishop Paula are tablemates at House of Bishops’ meetings, where he says he has developed “immense respect and affection” for her.

In August, Bishop Owensby and Nancy Bryan of Canticle Communications sat down via Zoom to talk about his upcoming visit to the Diocese of Chicago, when he will be the keynote speaker at diocesan convention, and how he thinks about Bishop Paula’s convention theme of “hope and connection.” The transcript of their conversation has been edited for clarity.

I’d love to start out by asking about when you have been to the Diocese of Chicago. Is there a story about a previous visit there that comes to mind as you think about being back in the diocese this fall?

Oh, yeah. My very last visit was for Bishop Paula’s ordination and consecration, and that was really so uplifting. Just the whole thing. To join in the celebration of her finally becoming bishop, it just did my heart good. The energy in that liturgy made me kind of envious, to tell you the truth, for what can happen at a liturgy. And it makes me anticipate a great good time at convention.

Can you tell me more about how the themes of hope and connection have come to be so central to your life and theology?

Sure. Honestly, all of us do theology in different ways. For me, the gospel makes sense when the rubber hits the road of real existence. And it’s in reflecting upon my life and upon the circumstances now and in the past of my life and our common lives that the gospel really starts to make some sense and becomes the animating force of my life. And that’s what hope is. And hope is the animating force of our lives. It’s God’s presence unfolding itself in our everyday existence.

Returning to my own life and why I think, as I look back on my life, hope became so central: I recently read an article in which a person who is the daughter of a Holocaust survivor said that those of us who grew up with a Holocaust survivor have experienced the effects of secondhand smoke. And I’m the child of a Holocaust survivor. And I think that profoundly influenced me, because my mother influenced me, and she learned hope in the camp. She learned that God would be present in even that most bleak and awful place.

We went through some rough times. My father was abusive. My mother escaped my abusive father and took me in tow. And that put us in some pretty trying economic circumstances. We were homeless for a while, lived in a car. And again and again, the example of my own mother offering hope in just her being and in her perseverance, her courage, just her capacity to keep going in the face of stuff, messy, messy stuff rubbed off on me. There are other influences as well. But those two things, as I look back, both the fact and sort of the legacy of my mother surviving the concentration camp and also her pattern of living, her leaning into life, her sense that God’s going to show up and we’re going to keep rolling here.

If were to put it in summary fashion, I’ve lived hope. I’ve lived it because I needed it, and I still do. I still do need it. It’s the animating force of my personal life.

In “Resurrection Shaped Life”, you call being human a group project. You go on in that section to say, “But [the apostle] Paul would remind us not to despair. Hope does not disappoint so long as we feed the hungry and shelter the homeless, so long as we refuse to greet the stranger as an enemy.” (p. 82) So hope and justice are two sides of the same aspect of faith, right?

I don’t want to sound terribly bleak when I say this, but the world isn’t as we dream it can be, right? If we participate in God’s dream, as our presiding bishop likes to say—God’s dream for us rather than the nightmare that we sometimes experience—we don’t just sit around and imagine it. It becomes real for us when we become the hands and feet of the God who’s dreaming.

And so doing the good that you can do today is also the way in which we know that God is at work. And I don’t mean to say something really crazy like I always know the mind of God or what I’m doing is God inspired, unlike everybody else. I don’t mean anything like that. What I mean is our source of hope—and this goes to the theme of the whole conversation I hope to have in Chicago—our connection is where the hope comes from, our connection to the divine, our connection to Christ, our connection to Christ and the Holy Spirit.

It’s knowing that God is present, not simply sitting alongside of us, but working in and through us to bring about a good that we could not have brought about merely by our own steam. It is what reassures us of, to use an old word, this whole providence thing: It’s for real.

Works of mercy and works of social justice, they are different things. I mean, social justice is work on the laws and the deep structures of our society, but they’re internally connected. So when I feed the hungry personally, I know I’m also connected to the larger work of God changing the algorithm of the creation. I’m waxing a little theological there. But the point is this, we act when we hope. We don’t just have a feeling. We’re doing something. Hope is praxis. People talk about faith being praxis. Hope is praxis. That’s where it becomes real. That’s where we know it. That’s when we are it.

One of the phrase that I underlined in your book was, “We are what we have grown beyond.” I’m curious how that plays out in community. How might a diocese find hope and connection in that growing beyond?

Leonidas Polk was the first bishop of Louisiana [Polk was a lieutenant-general in the Confederate Army and founder of both the Protestant Episcopal Church in the Confederate States of America and The University of the South]. So I stand in that line of bishops. In our work as a diocese, we’ve taken very seriously that healing the fractures and the wounds of racism is the work, is the community work, it’s the reconciliation work. But we’re partnering with the Roberson Project in Sewanee to engage and tell the truth about the legacy of slavery in this part of the universe.

In Colfax, Louisiana, not long after the end of the Civil War, there was a massacre. Former Confederate soldiers attacked a group of duly elected people and the people protecting them at the courthouse in Colfax. Dozens of people were murdered. Until very, very recently, it was called the Colfax Riot because the story that we were telling ourselves about ourselves is that heroic men put down a vicious riot. Well, what it was was a bunch of former Confederates and those who were sympathizers with them who wanted to overthrow a legal election. Gee, doesn’t that sound familiar? And they were successful. They were successful.

Our diocese is partnering with people from Colfax to tell this story through the Roberson Project, beginning to inch into the idea of oral history as a first step in getting the story straight in a broader way. In October we’re hosting an event that will feature Avery Hamilton, a Black minister whose ancestor was the first person murdered in the massacre, and Dean Woods, whose great-great-grandfather was one of the murderers.

We make connection first, establishing personal credibility, making it very clear that I will keep showing up. Isn’t that what God does, by the way? God keeps showing up. God keeps showing up, right? And I think when we’re the people of God, that’s what we do. We keep showing up, we keep caring. It keeps mattering.

I’m in my 12th year as bishop here and we’ve made some headway, but I know I’m going to be handing this off. It’s not done. It’s not going to be done, not in my episcopate. But you see that the reason I going to keep going is hope, right? God’s showing up here, and God’s people are showing up so that’s… Well, I’ll quit preaching now.

How does the work that folks in Louisiana are doing, the work with migrants that folks in the Diocese of Chicago are doing, how does this work increase our empathy and our hope and connection?

Well, you remember Martin Luther King, Jr. popularized Josiah Royce’s term “Beloved Community.” What King said was Beloved Community requires transformation of our structures and of our souls, right? Well, when we work together in that way, God is present and it transforms us. Relationship changes who we are. Human beings aren’t Lego pieces that you stick together or pull apart and they remain unchanged. We’re a web. Who we are is part of a web. And when we deepen those connections, we become more and more who we truly are.

When the Diocese of Chicago, just like the Diocese of Western Louisiana, engages the work that’s put before you, that work is the work of reconciliation. That work is the work of transformation. It’s what salvation is. Salvation is not celestial change of address, right? It’s being at unity with God and God’s people in a way that then transcends the limits of the grave. That’s what it is.

Beyond what we’ve talked about today, what is that good news that you are coming to share with the Diocese of Chicago?

One of the things I’m liberated from, and I really mean liberated from, is being innovative, creative, and new. I have an old thing to say. The kingdom of heaven has drawn near. There’s your message right there. The kingdom of heaven has drawn near, and what that really means is God is with us. The Christ message is that God is here now present always. Our work is to be aware of that. Yeah, I’m ripping off Richard Rohr, and I really don’t mind doing that at all. Our work is to be, through our practices, aware of the God who is near. And that awareness, and that’s why I said practices, our awareness is more than, “Oh, I see it.” It shapes and animates my life. When I am aware of God moving in me, I become who I most truly am.

And I become, Paul says, an ambassador of reconciliation. And I have to admit, I’m not real wild about that phrase, but I get the point. I prefer the Teresa of Avila quote, the hands and feet of Christ, right? That’s the message. The message is connection, right? The message is connection. That’s who we are as Christians. We’re Trinitarian. It’s relationships all the way down. And those relationships are not only vertical, but they are horizontal.

And that’s why I’m hanging on the phrase, the kingdom of heaven is drawn near.